Avoid extremely intense ideology: it cabbages up the mind.

|

| Munger & Buffett give thumbs-up to many things. But not extreme ideology. |

Charlie Munger warns of the dangers of too-strong ideology. He argues that “not drifting into extreme ideology is a very, very important thing in life.” And I agree. The saying, ‘where one stands on politics depends on where one sits,’ holds a lot of truth. It holds to a large degree in many areas of life beyond politics. It is not, of course, everything. And the determinism it suggests is frequently overstated.

No matter where a person sits, so to speak, in life, if where she stands on issues is determined by which newspaper she reads, she’s got a problem. Extreme ideology too frequently blinds people. I want to turn to Charlie Munger’s injunction not to be so blinded and then consider how ideology is contributing to some pretty bad results economics and journalism.

Munger asserts, “When you’re young it’s easy to drift into loyalties and when you announce that you’re a loyal member and you start shouting the orthodox ideology out, what you’re doing is pounding it in, pounding it in, and you’re gradually ruining your mind. So you want to be very, very careful of this ideology. It’s a big danger.”

And so it is.

Let’s consider a recent dust-up that puts this problem on display.

Some economists, vigorously disputed by other economists with equally good credentials.

|

| Economists Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart |

Economist Paul Krugman hits the Washington Post for being among those giving Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff “almost sacred status” and treating the economists’ findings “not as a disputed hypothesis but as unquestioned fact.”

|

| Economist Paul Krugman |

Krugman chided the Post, inveighing against the paper for warning against any relaxation on the deficit front on the grounds that the U.S. is “dangerously near the 90 percent mark that economists regard as a threat to sustainable economic growth.” Krugman takes especial exception to the phrasing: “’economists,’ not ‘some economists,’ let alone ‘some economists, vigorously disputed by other economists with equally good credentials,’ which was the reality.”

The left-leaning economist is certainly right about that.

|

| Thomas Herndon, U Mass at Amherst Doctoral Student. |

U Mass at Amherst doctoral student Thomas Herndon is straightforward about thinking the austerity movement in economic though & practice is wrongheaded. It’s hard to remain value-free in economics, at least about non-trivial topics. Researchers come equipped with biases—and that’s a good thing. Applying a scientistic technique won’t produce novel, interesting, or even, usually, accurate results in economics. Judgment is important. As Michael Oakeshott points out, “Nothing, not even the most nearly self-contained technique (the rules of a game), can in fact be imparted to an empty mind; and what is imparted is nourished by what is already there.”

This means that “a pianist acquires artistry as well as technique, a chess-player style and insight into the game as well as a knowledge of the moves, and a scientist acquires (among other things) the sort of judgment which tells him when his technique is leading him astray and the connoisseurship which enables him to distinguish the profitable from the unprofitable directions to explore.”

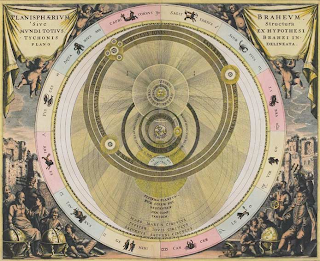

In a field as difficult and complex as economics, it’s ok if we sometimes wind up with theory that looks more like Tycho Brahe’s Geo-heliocentric model than a more accurate pure heliocentric model. Tycho had access to the best instruments in the world. And he was meticulous in recording accurately the movements he saw in the heavens. But, ideologically, he was a bit wedded to the idea (also popular in church circles during his time) that the Earth was the center of the universe. So, despite his accurate measurements and calculations, he came up with a theory that used good data to support an idea that those measurements should have outdated.

Postulate any interesting theory and you run the risk of being wrong. There are no guarantees. If you’ve got some economic theories you’re dying to get out there, just be glad that, unlike Tycho, you’re unlikely to get your nose cut off or your body exhumed to determine whether you died of poisoning.

|

| Tycho Brahe's Geo-heliocentric model. |

Economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff have been hugely influential in the economic and political theory & practice of late. The authors published a 2010 paper that argued that economic growth suffers in countries whose debt exceeds 90 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Politicians got hold of their paper…and ran with it. The Reinhart/Rogoff paper was used extensively to justify austerity measures in nations that have, to be charitable, troubled economies.

The New York Times’ Paul Krugman, and other economists who disagree with austerity on ideological grounds, didn’t love the paper. Or the politics it engendered (or better, the justification for that politics, which existed long before the paper, and such measures would have been advanced, though probably using different justificatory arguments). Critics charged the paper with many things, most damagingly, that it didn’t demonstrate causality, and that it didn’t show how climbing debt and economic slowdown interacted.

Krugman observed that, “many economists pointed out that a negative correlation between debt and economic performance need not mean that high debt causes low growth. It could just as easily be the other way around, with poor economic performance leading to high debt.” And points to Japan of the early 1990s as a case in point.

Selective and unconventional, yes. Good economic theory, no.

Critics on the left said the paper is ideology, not social science. And I think there’s far too much truth to that. But Herndon admits to entering the affair with a pretty well-established ideology, too. Why did he do better? While the third-year graduate student was working on an econometrics paper he attempted to replicate Reinhart’s and Rogoff’s results. Using the material publicly available, he couldn’t. So, smartly, he asked the authors to provide more. They did. The economists sent Herndon their spreadsheets.

Herndon, partly because of ideological differences, was skeptical from the start. But he didn’t just question the ideology; he examined the data. And he wound up finding errors with those data. The problems he found center on data that look at countries' economic growth and debt levels. As Krugman summarizes: “the mystery of the irreproducible results was solved. First, they omitted some data; second, they used unusual and highly questionable statistical procedures; and finally, yes, they made an Excel coding error. Correct these oddities and errors, and you get what other researchers have found: some correlation between high debt and slow growth, with no indication of which is causing which, but no sign at all of that 90 percent ‘threshold.’”

Not surprisingly, Herndon’s working paper got noticed. In a conversation Herndon had with the Chronicle of Higher Education he said, "The terms we used about their data—"selective" and "unconventional"—are appropriate ones. The reasons for the choices they made needed to be given, and there was nowhere where they were."

(Sometimes, when trying to avoid the ravages of extreme ideology, it helps to have a sense of humor. See video below).

This is more than an academic issue. And, while its consequences have so far mostly been felt in Europe, the debate is moving closer to home for the U.S. Paul Ryan's Path to Prosperity budget claims to have "found conclusive empirical evidence that [debt] exceeding 90 percent of the economy has a significant negative effect on economic growth."

Abusing Parminides

|

| Greek Philosopher Parminides |

Greek thinker Parminies held the following precept: judge by rational argument. And I think there’s a way to look at things rationally without falling into the trap of thinking that there’s no way anyone who can think honestly and clearly will always agree with me. Munger is right, clinging to a too-strong ideology almost always leads to a ‘cabbaged’ mind. The problem isn’t about technique, really. It’s not about using Excel properly (though that would help). It’s about not letting ossifying ideology get in the way of intellectual honesty.

And Munger has some pretty good practical advice: "I have what I call an iron prescription that helps me keep sane when I naturally drift toward preferring one ideology over another and that is: I say that I’m not entitled to have an opinion on this subject unless I can state the arguments against my position better than the people who support it. I think only when I’ve reached that state am I qualified to speak."

No comments:

Post a Comment